Keep scrolling past the first article for the video description of the Tacoma, Washington shipping project.

The Evolution of “The High Capacity One Pass Wheat Cleaning System” Author: Steve Cashman with R. Van Sickle and Bert Farrish

In the mid-1990s the largest US export market for Hard Red Wheat (HRW), Japan, changed its grain quality specification from a maximum dockage/FM (foreign material) content of 0.5% down to 0.3%. Suddenly the US grain companies were unable to compete with the Canadian shipping quality as no US grain shipping facility could meet the new quality standard. However, the problem quickly became an opportunity for worldwide manufacturers of grain cleaning systems…the race was on!

This sent a shock wave through the US grain markets as the potential loss of the Japanese market would severely reduce the export of HRW. The large grain companies and major exporters with ocean-going shipping facilities including Cargill, Columbia Grain (owned by a Japanese trading company Marubeni), Con Agra, Louis Dreyfus, and ADM did their best to mandate the new quality specification on their suppliers in the hinterlands in the northern HRW growing states along the Canadian border, but with no avail, as very few of this country grain facilities were outfitted with wheat cleaning equipment to meet this new standard at the shipping volume required.

So they were stuck without the ability to meet the new standard as their outdated method of cleaning grain over rudimentary screening devices and then blending lower dockage lots with higher dockage would not allow them to meet the new standard. The real problem, they discovered, was that to clean down to less than 0.3% FM/dockage the system would have to remove large dockage/FM, including the notorious WILD OAT component, something the Canadian Wheat Board and their grain handling facilities had been able to accomplish for years, but on a slow process rate of flow.

So what to do? After the grain companies determined that they could not require their suppliers (many of which they owned) to clean and ship the grain to the export facility, at the new cleanliness and at the volume required at the shipping terminals for direct shipping to Japan. The cost of the equipment and infrastructure changes would be prohibitive. They had no other option but to clean the grain at the larger export facilities in the Northwest.

Note: This section was written by my friend, Steve Cashman, who I thought would have a more accurate recall of specific details, especially of the technical terms involved. As it unfolded, Stave had more than that. He had some very interesting added features, requested by: Dick VanSickle.

Columbia Grain, headquartered in Portland Oregon, owned by the Japanese company Marubeni, was keen on investing to meet the needs of their parent company, along with the Japanese flour millers. To investigate the opportunity further, they hired an engineering company in Minneapolis, MN, Van Sickle, Allen and Associates, Inc. (VAA, Inc.) to research process equipment providers and to design a system to meet this new specification. This proved to be no small task!

They contacted several of the prominent grain cleaning equipment manufacturers in the US and Europe to discuss the specifications including Buhler, Inc. in Minneapolis, MN. While Buhler’s expertise was in providing grain cleaning and milling systems for much lower throughputs they were keen to provide a system that would meet the needs required.

Buhler quickly designed and proposed a system that would clean the wheat at the desired capacity (40,000 bushels per hour BPH) and to the required quality specification of less than 0.3% dockage/FM. However, it would require over 30 machines, a large new building, and enough horsepower to light a small town. The overall costs associated with such a solution were cost-prohibitive and an operational cost nightmare. Knowing that the objective was possible but needed to provide a higher throughput capacity, it was “back to the drawing board”.

At about that time, in July of 1995, Steve received a phone call from an old friend and neighbor, Tom Rider, who was working for Van Sickle Allen & Associate’s firm (VAA, Inc), explaining to him their new project and asking if I had any ideas as to a system that might meet this very aggressive performance specification.

I had been in the grain cleaning equipment manufacturing industry for over 20 years and had just returned from Europe (Austria) where I had been managing a grain cleaning equipment manufacturing company, Cimbria Heid GMBH owned by Cimbria Manufacturing in Thisted Denmark.

I shared with Tom that I had accepted a position as Director of Sales and Marketing for the parent company Cimbria and that they had made a recent decision to design a new line of high-volume grain cleaning equipment for the US. The timing for this opportunity was perfect as we would need a beta site to introduce our new line of high throughput grain cleaning machines.

However, the very aggressive specification (to reduce an average of incoming dockage from 1.25% to less than 0.3%) would require the additional removal of larger foreign material/dockage including short strat, WILD OATS, which would present a real challenge based upon the higher flow rate of 40,000 BPH.

I capitalized and underlined WILD OAT because, to date, no system in the world could remove WILD OATS from wheat at that high level of throughput without employing a plethora of low-capacity length separators used specifically for this application. Consequently, that would make the system very costly and the space required virtually impractical.

To learn more about the application and present his ideas as to a possible solution, Tom invited me to their (VAA, Inc.) offices in Minneapolis. The meeting was held over lunch so after probing the project engineers on the application, they proceeded to enjoy their bag lunch while I provided some systematic grain cleaning concepts for their education benefit. Note: VAA, Inc., would invite sales and engineering people to present application solutions over the staff lunch hour, and their brown bag seminars, to gain knowledge of new process equipment and systems without cutting into their workday productivity.

About halfway through the hour, Dick Van Sickle joined the group and sat on the floor a few feet from my sales podium. As the hour ended, Tom Rider thanked me for my presentation and all the engineers and designers left the room and went back to work, albeit with a full stomach, but as Steve remembers, without a practical solution.

Dick waited until everyone had left and asked if we had had any lunch? We told him no, but it wasn’t a problem as I had eaten a late breakfast. At that point, he reached into his lunch bag pulled out half of a huge sandwich, and gave it to me. I had to say I was surprised by his generosity and thanked him for his kindness. Steve remembers and enjoys retelling this part of the story “Dick introduced himself and went on to provide me with a much clearer understanding of the project, the players, and the opportunity in the overall grain industry. We became good friends which was the best part of the experience for all of us.”

Fast forward to January 2023, Dick is writing his book with a thematic approach and called Mark Avery for help on this one.

To tell this story better, Steve’s experience in earlier tests was as follows. Fourteen years ago, Steve was working for Cater Day, Inc. in Fridley, MN as Director of Sales and Marketing as well as managing the R & D where they were testing a new rotary screening machine that they were developing for seed cleaning and grain processing applications. The test machine employed a single screen deck surface used to study the material flow and efficiency of separation as compared to the reciprocating screen motions commonly used for these applications.

That particular day, Steve was asked to come to our R & D building to witness the operation. To get a better look at the screening action and the material flow, I went to the mezzanine level of the building to look down on the machine’s screen surface was a small wire mesh used to remove undersized foreign material from hard wheat. He also noticed the larger/longer wild oats bubbling up from the grain mass as the wheat moved downward and along the screening surface.

As the wheat dropped off the end of the screening deck, the wild oats appeared to be riding on the top of the grain bed. He recalls commenting to their development engineer that the lower-density wild oats appeared to have been moved upward by the higher-density wheat forcing them to the top of the grain bed. This was similar to a “Fluidized” bed separator but without using an industrial air component!

He went back to his office and made a summary of his observations and put that experience in the memory bank for a while.

Jumping back to the meeting with the engineers at VAA’s offices, he returned to his office. He wrote a note to the manager of R & D Soren Madsboll in Cimbria’s Denmark offices about the opportunity to precision clean wheat down to 0.3% dockage at a rate of 40,000 BPH.

As I mentioned, their company was in the process of designing a new line of high-volume screening devices and employing a screening deck design that would use each screen deck which included both sifting screens that removed small dockage/foreign material and scalping screens with larger openings to remove large sized dockage/foreign materials in a series. That was for them and the grain cleaning industry, a new concept.

He explained to Soren his observations from long ago regarding the “floating off” of wild oats and asked him to test the idea in his research facility. After some initial reluctance, he agreed to run a simple test. He called me early the next day and informed me that what I had described and had observed 14 years prior was duplicated – much to his amazement – and the concept of “floating off” wild oats and other dockage/FM was “hatched”.

We then put together a conceptual flow diagram utilizing 4 of our largest, newer style MEGA Cleaners (Model 168), which ”get this”, he said, were not yet fully engineered! Each of these machines had an inlet capacity of 10,000 bushels per hour of wheat. We planned to run them as a group, followed by a batter of 4 – Model 10620 “Cimbria Heid” separators used to reclaim the wheat from the “floated off” wild oats, and other oversized foreign material.

Van Sickle Allen & Associates project team was very excited about the prospects of employing this system as the overall project cost would become feasible and the space required would fit easily in the spaces normally available at Grain Export facilities, and, even better, utilizing only about 10% of the electrical power anticipated.

The only question then, was, WOULD IT WORK?

At that point VAA arranged a meeting in Portland to introduce the concept to the Columbia Grain Operations and managing team and their Vice President of Operations, Bert Farrish.

After Steve had reviewed the equipment specifications, performance expectations, and process capabilities with Bert and his staff they too became excited about the opportunity and the prospects of being the only US grain company that could provide HRW wheat into the Japanese market that would meet their new specification which was enticing.

Note: The Canadian grain companies could meet the specification but the process costs to do so far exceeded the cost associated with this new system.

After the meeting, Bert presented to his corporate management and his parent company, Marubeni, which raised the eyebrows of a few skeptics. The questions then centered around whether Cimbria would provide the process guarantee. That is, to say, would they agree to be “on the hook” if this process idea implodes?

To ease some of the tension, Cimbria agreed to conduct a full-scale test (using 1/4th of the system at a flow rate of 10,000 BPH) utilizing the exact machinery designed for the process. If the test results were positive Cimbria would guarantee the cleaning performance but not a complete process guarantee!

To ensure that the dockage type and mix were typical, Columbia Grain sent several tons of HRW (wheat) to Denmark, with actual/typical dockage which was to be used for the testing.

We then put together a team of stakeholders including myself, Dan Stutz, Terminal operations (at the T5 terminal), and Gene Haldorson from VAA to travel to Thisted, Denmark to witness the testing. (Dick is not sure Gene went along!).

The testing went very smoothly as the results indicated that the specification could be met with some comfort level. The heartening observation was the fact that the percentage of removal of the wild oats, employing the “float off” concept, was close to 100%.

The results were compiled and provided to VAA and Columbia Grain but Cimbria would only guarantee the performance of each of their machines and not the entire process. If for some reason the system performance overall did not meet the design specification, Cimbria was off the hook. This would be accepted by the operations management of Columbia Grain but was not by the corporate managers.

At that point, we were all at an impasse so Steve offered to put together a detailed presentation with flow diagrams from each component of the system. The corporate managers agreed to the presentation.

Before the meeting, Bert gave us an overview of the managers attending, their authority, and their attitude regarding the project. He warned me that the grain operations director was dead set against the project and their relationship had suffered as a result. He also mentioned that he was highly combative, so beware.

As Steve entered the meeting, he could sense a high level of tension, it was as if the devil himself had entered the room, he recalled. Bert introduced Steve to each of the attendees and no one thanked him for coming. The last introduction was to the director and he gave the coldest look Steve had ever received in his sales career. As he worked through the presentation, only the director spoke asking him, after every process description, how he was sure the results would mirror the system we proposed. He could only relate the findings of Cimbria’s testing and because this was a beta site, we had no full process experience. This did not sit well and the comfort level of the room continued to drop as he went through the process performance.

When the presentation ended, Steve asked if anyone had any further questions and only the director spoke out saying, “I will be damned if we are going to be someone’s Guinea Pig” and he left the room followed by his dutiful minions.

As Steve walked out of the meeting with Bert, he thanked him and said, “I feel like I have been ridden hard and put away wet”. He said he felt worse than that!

The battle was on within the Columbia Grain management as to whether they would install something more conventional which most likely could not meet the cleaning specification, or risk putting in a non-conventional system that looked good on paper and tested well in a full-scale lab setting, but was unproven, built in Europe, and without an acceptable process guarantee.

After much in-fighting, Bert Farrish, the President of Columbia Grain Company, by then, was able to convince his very reluctant corporate management that after much analysis the only solution that was remotely feasible was Cimbria’s one pass wheat cleaning system employing the revolutionary but untested wild oat “float off” system.

Columbia Grain signed a purchase agreement in February of 1997, 19 months after the initial meeting at VAA.

One year later, the system was started and after some initial issues in achieving the flow rate, the system performed to the exact wheat cleaning specifications as was stated in the initial testing 2 years earlier.

The Cimbria “One Pass Wheat Cleaning System” utilizing the unique “Wild Oat Float Off” concept, became the industry standard process in high-volume precision wheat cleaning for years to come.

Article by Steve Cashman with contributions from Bert Farrish and Dick Van Sickle (Retired group members).

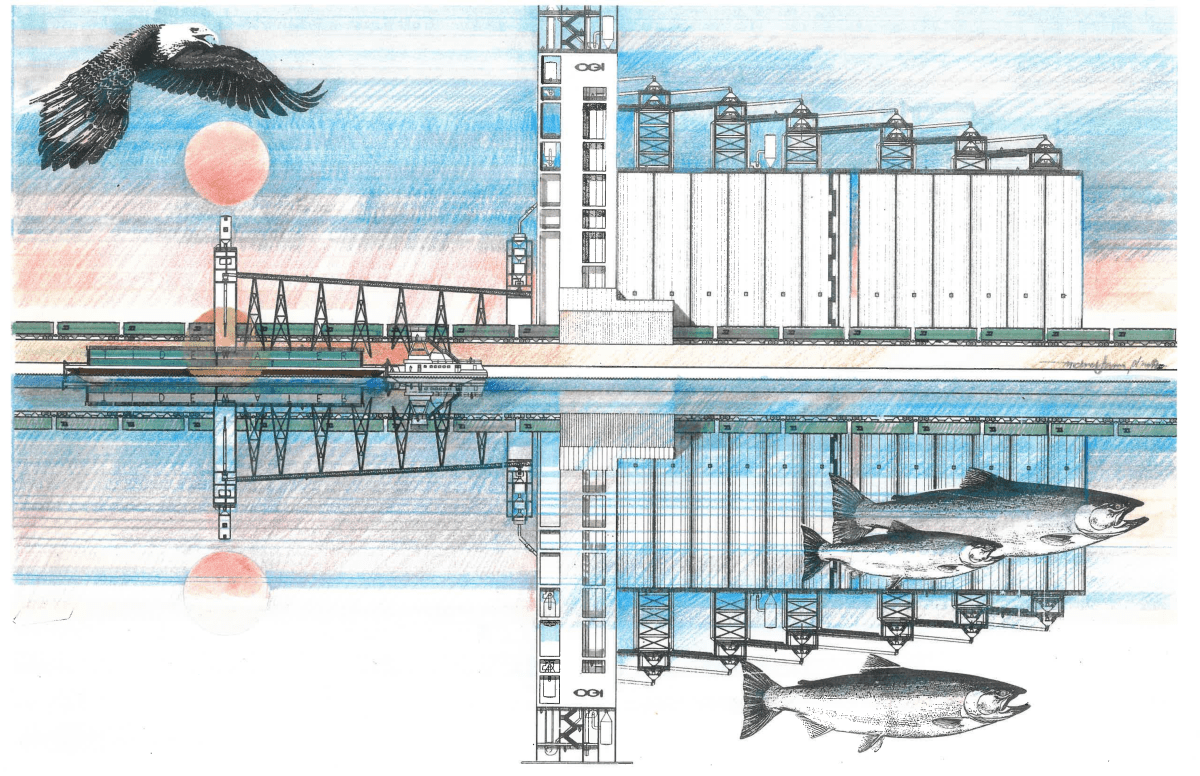

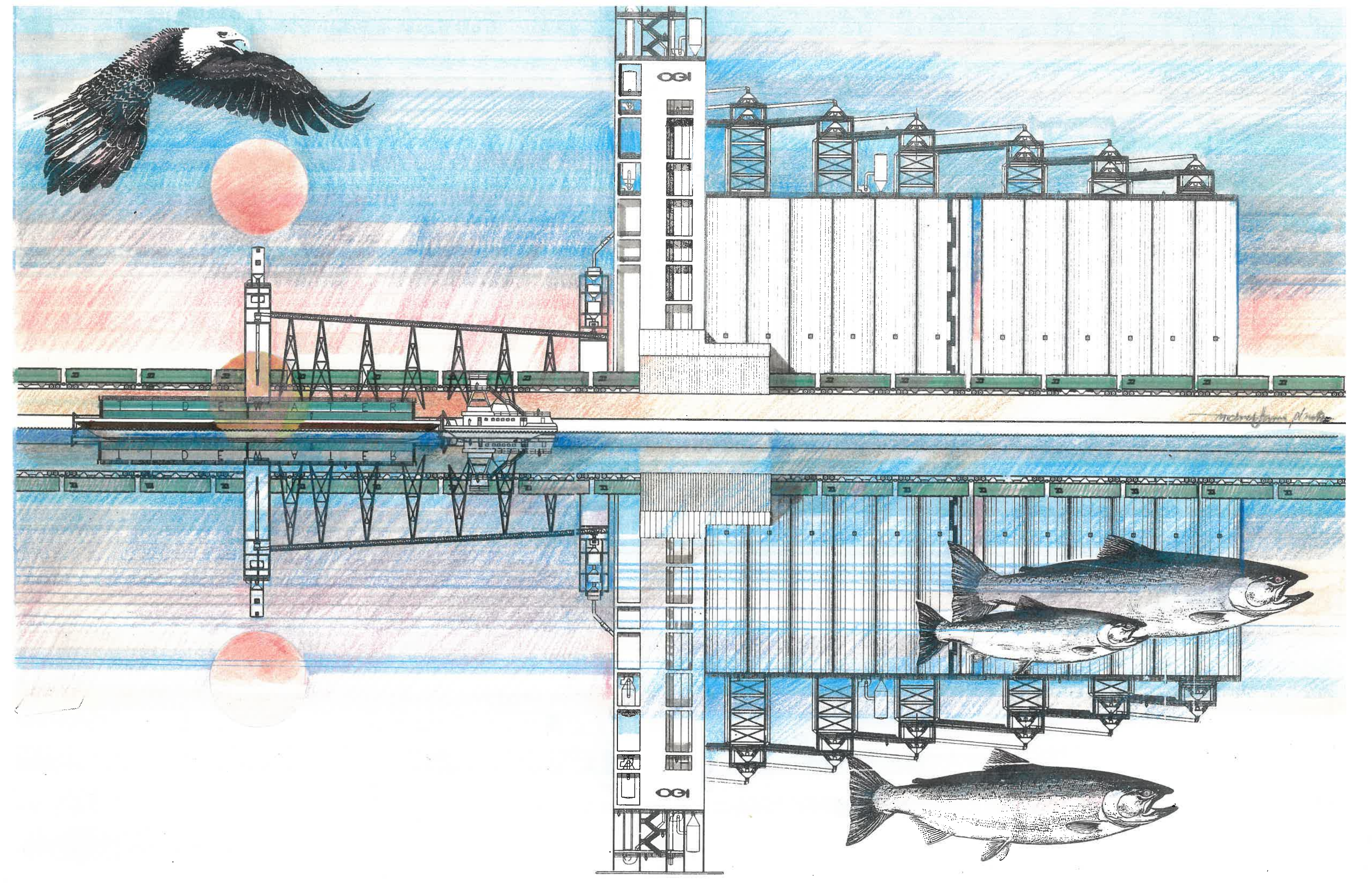

Tacoma, Washington Project – A cantilever roof for protecting grain loading.